Is this Dracula’s grave? It was perfectly comfortable – a good fit too. Apparently one of the most common questions asked by tourists in the charming town of Whitby in North Yorkshire is ‘where is Dracula’s grave?’

Dracula apart, there are plenty of other attractions in Whitby with its picturesque harbour and quaintly narrow streets as I found out on my recent visit there.

There is locally made jet jewelry, native to these parts and, dare I say it, nice’n Gothic, jet jewelry. It would look good around Lucy Harker’s neck. Who’s Lucy Harker? you ask. Come on, you obviously haven’t read the book or even seen the films.

For a change of subject, I looked in the shop window of Justin’s, makers of fine chocolates, and look, the evil Count is even in there. A pointed stake is a good idea for your hand luggage if you plan a visit.

There’s a lovely view of the harbour as you climb up the 199 steps to Whitby’s most famous building.

Captain James Cook (1728 – 1779), the man who discovered all those bits on the world map that we didn’t know about until he came along. His ships were built here too. Methinks, so that’s where Dracula arrived in Whitby, I thought. You remember when his ship sank on the way to London and he swam ashore disguised as a black dog.

It’s a long climb to get to the spot that everyone wants to see. These are called Church Steps and they take you up to the 12th Century church of Saint Mary’s with it’s interesting architecture and its spooky graveyard. No one is saying it but they all want to find Dracula’s grave.

If you think that you’ve been here before then it’s because you’ve read the book:

‘For a moment or two I could see nothing, as the shadow of a cloud obscured St. Mary’s Church. Then as the cloud passed I could see the ruins of the Abbey coming into view; and as the edge of a narrow band of light as sharp as a sword-cut moved along, the church and churchyard became gradually visible… It seemed to me as though something dark stood behind the seat where the white figure shone, and bent over it. What it was, whether man or beast, I could not tell.’ (Dracula by Bram Stoker, 1897)

Those ruins are the remains of Carfax Abbey, whoops, sorry, that’s somewhere else, I mean Whitby Abbey, an important historical site. The abbey was founded in 657 AD as an Anglo-Saxon “mixed” monastery. ‘Mixed’, a bit like in saunas, means that monks and nuns co-habited here in the glory days of the Celtic Catholic Church. Tut tut, I hear you say. It was the site of the, er, famous Synod of Whitby in 664 AD and ecclesiastical gathering that agreed to change the dates for Easter so that they coincided with the Roman Catholic Easter but it also marked the moment when the Celtic Church finally lost out to the Roman Catholicising of England. However, not many of the visitors who made it up all those steps were there to remember the Synod of Whitby. The first Abbey was destroyed in a Danish invasion and the new one was built as a Benedictine, men only, monastery.

The abbess at the time of the Synod of Whitby was none other than Saint Hilda (614 – 680), a fine woman of resolute belief and kindly ways who encouraged, a simple soul called Caedmon (657 – after 684), the guy who looked after the abbey’s animals. While Hilda was abbess, this Caedmon discovered that he could not just be kind to animals, he could also write poetry. He became the earliest known English poet.

Caedmon is buried in St Mary’s churchyard but, apparently, not many visitors to the Abbey care about that. People all want to see the Abbey’s ruins – not because of King Henry VIII’s act of vandalism when he “dissolved” the monasteries. in 1540. Upsetting though it is thinking about the magnificent building that was destroyed, you have to admit it makes a mighty fine ruin.

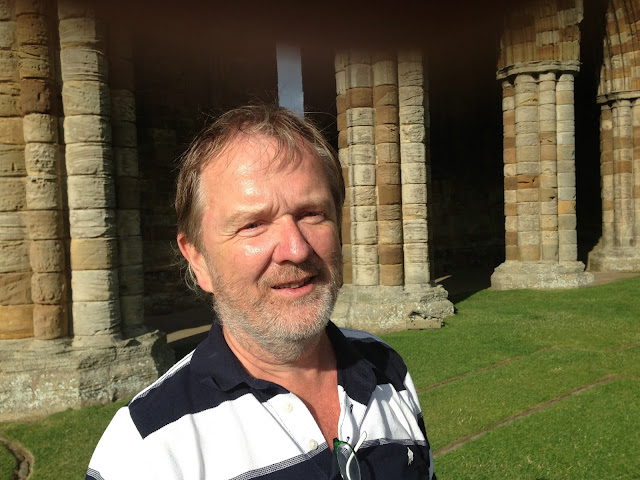

I was accompanied to Whitby Abbey by that close relative of mine, Henry Bell who is now living down the road from here in Scarborough. He, like me, was keen to see if we could find Count Dracula’s grave, no, I mean we wanted to find out about some of the other interesting historical facts about the place. The site is now maintained by English Heritage so you have to buy tickets to get in but that’s fine by me, it’s very important that our heritage is preserved.

http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/whitby-abbey/

I noticed that ticket prices varied depending on whether you were a child, a student, an old person or just an average Joe. You can also take out a life membership to English Heritage while you’re there. Now this made me wonder. Supposing, I thought, we were to come across the Count while we were visiting and supposing he did his evil worst with us, would English Heritage do a special deal with life memberships for the living dead or would that be financially ruinous. I asked the helpful ticket salesman about this but, disappointingly, he said that it wasn’t English Heritage’s policy to offer concessions to the undead. Shame.

The ruins are magnificent and there is still enough standing to imagine what a splendid piece of architecture was lost when England went all peculiar over churchey things.

It’s still a powerful experience walking through the remains and admiring the craftsmanship of those medieval stone masons.

On a sunny summer’s day, the blue sky gives the old abbey a more beautiful ceiling than any work of man.

Those drifting summer clouds too make wonderful alternatives to the destroyed stained glass windows.

It was all enough to let you, almost, forget about the ruin’s most famous visitor.

I mean the Irish writer, Bram Stoker (1847 – 1912) who came to Whitby in 1890 with his family to admire the views but then had a very inspired idea. He was manager of the famous actor Henry Irving’s Lyceum Theatre in London for 27 years and where he was also a friend of Oscar Wilde and Arthur Conan Doyle but his fame sprang from one inspired idea.

Stoker loved the atmosphere of the town and was particularly taken by the Romantic atmosphere of the ruined abbey. It inspired him in writing his most famous novel.

When he arrived in Whitby, Stoker had already begun his vampire novel but then his main character was called Count Wampyr. I suppose anyone called Bram is going to struggle over sensible names. He was doing research in Whitby Library when he found a book, An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia (1820) by William Wilkinson. In that interesting tome, he read about a man called Dracula who fought against the Turks. In his notes, Stoker also added this, probably the first mention of his famous character: ‘Dracula in the Wallachian language means Devil.’

I don’t want to spoil the story for you but, as you can see, Whitby Abbey would be a good place for a vampire to lie in his coffin during the hours of daylight. I’m not sure how many of us would volunteer to spend the night there on our own.

Don’t let me frighten you away from Whitby though, it’s a lovely town and well worth a visit. Just don’t forget to pack some garlic. It was disappointing not actually locating Dracula’s grave. No one in Whitby would tell me – not even the woman in the Whitby Museum. She said nobody knew – pfft, believe that and you’d believe anything.

Dracula, the book, became a worldwide best seller and, in the 20th Century it became a natural for the cinema. First with an unauthorised Expressionist adaptation by the German director F.W. Murnau starring a truly terrifying Max Schreck as the Count, here renamed, Nosferatu.

A new Dracula is about to be unveiled with Jonathan Rhys Myers in the title role. If you are one of the few people who have never seen a Dracula movie, here’s some preparatory study before the NBC Dracula television series airs this Autumn. Let’s hope that Jonathan is up to the challenge.

The original, Nosferatu (1922), is still the Dracula of our nightmares and remains in the mind forever once seen:

It was a hard act to follow but, in 1931, there was my favourite Dracula, the immortal Bela Lugosi in the film directed by Tod Browning with Dwyte Frye as the unfortunate Rennfield:

German director Werner Herzog attempted the impossible in 1979 in his remake of the 1922 Nosferatu with Klaus Kinski as a very cinematic Dracula with Bruno Ganz as Jonathan Harker:

.jpeg)

.jpeg)