As I work my way through the history of Western classical music (I have written before how I dislike the phrase classical music but enough of that for now), I welcomed in 2011 the other day with my own new year celebrations for reaching, musically, 1871. 1870 had been dealt with pretty promptly as it was a bit of a barren period – except if you are an enthusiast for the ballet music of Leo Delibes or the also-ran symphonies of Joachim Raff. The big event of that year was the first performance of Brahms’ Alto Rhapsody, written in 1869. Brahms was 36 and still anguished over his growing belief that he had to devote his life to his art even if that meant sacrificing love. His despair might have been made worse because he may have been repressing and over-simplifying something psycho-sexual that he wanted to hide. The young Johannes Brahms may have been sexually abused by the prostitutes that worked the bars where the child pianist played for money. If that is true it might explain why, throughout his life, he made a separation between the women whom he adored platonically and the prostitutes that he paid for sex.

By 1869, he could see that he might never be happy in any relationship so he was ripe to pour his feelings into one of his first truly great masterpieces – the Alto Rhapsody, a setting of part of a poem by Goethe for mezzo-soprano, male chorus and orchestra. The score of which he apparently kept under his pillow at night for the rest of his life.

The poem, Harzreise Im Winter (A Winter’s Journey In The Harz), concerns that great image from German Romanticism, the Wanderer. In the poem and in the music, this wretched man is sent into extremes of depression and pain by some unspecified experience with love. Brahms writes what could be a scene from an opera – the nearest he ever got to operatic passion.

The piece is for me the first of Brahms’ works that I would not be able to live without and it heralds the fact that he was about to write his first symphony and to claim his throne as the greatest composer of the late Nineteenth Century.

I spent some of the Christmas holidays playing with my new computer and trying to work out how to edit pictures to music. Nothing seemed more appropriate than to have a go at illustrating the Alto Rhapsody with some of my favourite 19th. century paintings – here the mystic landscapes of Casper David Friedrich and the outrageously narcissistic self-portraits of Gustave Courbet.

Goethe’s German poem is printed below with an English translation so don’t be like a friend of mine who says that she doesn’t listen to vocal music very much because she can’t be bothered to read the text or its translation. Great words and music come together in this piece to inspire anyone who takes the time to listen.

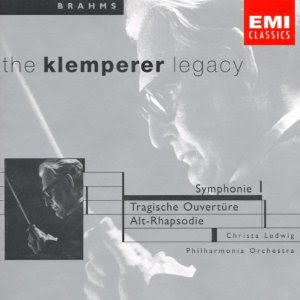

The recording, still available on CD, is an inspirational 1962 performance with the German mezzo-soprano Christa Ludwig (one of the greatest 20th. Century singers) with the Philharmonia orchestra conducted by the incomparable Otto Klemperer who was twelve years old when Johannes Brahms died.

If anyone enjoys this, I might do some more to illustrate the music that I am studying. Let me know.

Thank you for your deeply felt show. Christa Ludwig is wonderful, Kathleen Ferrier so much deeper. A very modern, disturbing and comforting poem by one of Europe's greatest.

Thanks for your kind comments Ingela – I'm delighted that you enjoyed my little film.