Camille Saint-Saëns (1835 – 1921)

“He knows everything, but lacks inexperience” (Il sait tout, mais il manque d’inexpérience) said Hector Berlioz in one of his wittiest musical put-downs when talking about the brilliant young French composer Camille Saint-Saëns who, with Mendelssohn, was probably the most naturally talented child prodigy in musical history. It all came easily for little Camille but, for a genius, he has failed to establish himself on posterity’s list of musical very greats. Berlioz was probably right – in the end Camille Saint-Saëns may have been a victim of his own prodigious talents exercised throughout a remarkably long musical career.

Of course, he is not forgotten – far from it. We all know more of his music than we realise. Come back to the following musical clips when you have time and you’ll see what I mean.

1) The lovely cello solo depicting a swan from The Carnival of the Animals (1886):

2) Even if we don’t realise it, most of us know Delilah’s great song of seduction from his opera Samson and Delilah (1877), Mon coeur s’ouvre a ta voix:

There is an extraordinarily large amount of music that people are less familiar with and, if I can persuade you, take a look at some of his piano concertos where his lyricism, technical wizardry and mastery of form come together in works that stand high in the Romantic music of the second half of the 19th Century. The violin concertos, especially the 3rd, should be on everyone’s listening list too. We should remember that the old buffer in the later photographs was once the young lion of French music. The “French Beethoven” according to Liszt who acknowledged his place with the progressives, Berlioz, Wagner and, yes, Liszt himself.

He fought, almost single-handedly, to revive instrumental music in France in an era when French opera almost obscured any other works by French composers – Fauré, Chabrier and Ravel acknowledged their debt as did composers from other countries, Tchaikovsky in particular. He was, without doubt, a very clever man, an authority on geology, astronomy, philosophy and mathematics who wrote a philosophical treatise that is said to predict existentialism and who commissioned an astronomical telescope to his own specifications. He was also a life-long collector of butterflies. Unlike many classical musicians, he had what is known as a hinterland. Some might say that he was too clever by half.

French astronomer Camille Flammarion (1842-1925) with Camille Saint-Saëns in Flammarion’s study in 1921.

At the age of two, it was discovered that he had perfect pitch; by three (1838), he could read and write, pick out melodies on the piano and he had also started to compose, music. By the age of five he had given his first piano recital and when he was ten he made his debut as a concert pianist, performing a Mozart’s Piano Concerto in B flat, K595 and Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto. For an encore, he offered to play any of the thirty-two Beethoven piano sonatas from memory.

He wasn’t just a piano virtuoso, Liszt called him the greatest organist of the 19th Century and this brings me, at last, to the point of this blog. I have reached the year 1886 in my chronological journey through the history of classical music and I have got stuck on Camille Saint-Saëns. There is The Carnival Of The Animals that year, written for the private amusement of his friends but there is also the great Third Symphony – Symphony No. 3 in C minor (with organ) as it was known officially but we all call it the Organ Symphony even though it might be more properly called the “keyboard symphony” as it also has parts for piano, both two hands and four hands. I’d always been impressed by this piece but, this week, I’ve got obsessed with it and I can’t stop playing the performance on a newly purchased CD. It not only has that sensationally dramatic finale where the organ challenges the orchestra (and piano) to thrilling effect but it also has one of the most lyrically beautiful slow movements in the symphonic repertoire and a whole lot more besides. The whole work is united in Lisztian style with the cyclical use of variations on a theme. If you don’t know it, then, honestly, you don’t know what you’re missing. even the great man himself said of it: “I gave everything to it I was able to give. What I have here accomplished, I will never achieve again.”

Camille Saint-Saëns playing the piano (1910)

Maybe, he knew that his long career as a composer of orchestral music was coming to an end so he threw everything in his composer’s armoury into the work and, maybe, he was right, maybe it is his greatest piece. I’m proud of England’s grand old Royal Philharmonic Society who commissioned the piece (as well as Beethoven’s 9th Symphony and Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony) and invited the composer to London to conduct the first performance in 1886 – dedicated, naturally, to Liszt who had died that year. I’m thrilled too that it took America’s Philadelphia Orchestra to revive my enthusiasm for this work in one of the most exciting and beautiful recordings in my CD collection. It was recorded live in Philadelphia’s Verizon Hall on the inauguration of its concert orchestra (the largest in the USA) and it’s simply terrific – not just a barn-stormer with the organ allowed to go berserk but a performance that allows space and time for Saint-Saëns’ always inventive orchestration and as impressive in the quiet moments as in the great climaxes. We are allowed to appreciate the composer’s unequalled “ear” in all the orchestral effects and the result is the equivalent of the great restorations of Old Masters’ paintings.

If you don’t take my word for it, this is what the critics said. I don’t usually look at the reviews but I had to check that I wasn’t just in need of going out more:

“…it is a breathtaking achievement. There is passion, but precision, technically well-nigh faultless.” –BBC Music Magazine, March 2008

“The inauguration of Verizon Hall’s new organ has been preserved for all of us in one of the most outstanding SACDs yet. Somehow, producer Martha de Francisco and her team (assisted by Polyhymnia) have captured the detail, sweetness, and power of the orchestra, as well as the organ’s pipes and pedals, in a recording that is more than a sound spectacular.” –Stereophile Magazine, May 2007

.jpeg)

“The organ shows its stature (the booklet tells us that, with 6938 pipes, it is the largest concert hall organ in the US) with palpable depth in the first movement and majestic presence in the finale; but the real star of the show here is the Philadelphia Orchestra itself. Mouth-watering wind solos, gorgeous string-playing and a wonderfully crisp and cohesive sound (as it must be in what sounds a dreadfully dry acoustic) combine to create rather more memorable moments than we have a right to expect; the string entry just before the close of the first section is, as they say, to die for.” –Gramophone Classical Music Guide, 2010

So, let’s celebrate a great recoding and the great Camille Saint-Saëns – infant prodigy, young lion, bon viveur, wit, great composer and man of the World. A man of mystery who enjoyed dressing up in women’s clothes, who abandoned his wife after the death of their two sons finding secretive solace in Algiers, the Canary Islands and Egypt and who lived long enough to be forgiven for his later life as an intriguing mix of fun and curmudgeonliness who called Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (1913), “mad” and who said of Debussy’s opera: “I have stayed in Paris to speak ill of Pelléas et Mélisande.” (1898). Like his composer predecessor, Giacomo Rossini, he knew how to make us laugh too.

I can’t play you a clip from that wonderful recording of the symphony but you can buy it here:

Meanwhile here’s an earlier Philadelphia Orchestra performance of that spectacular last movement, conducted in rollicking style by Eugene Ormandy with Michael Murray playing the Haskell-Shultz Organ at the Church of St. Francis de Sales in Philadelphia. If you’re wearing socks, be warned, they’re about to be blown right off.

—————————————————————————————————

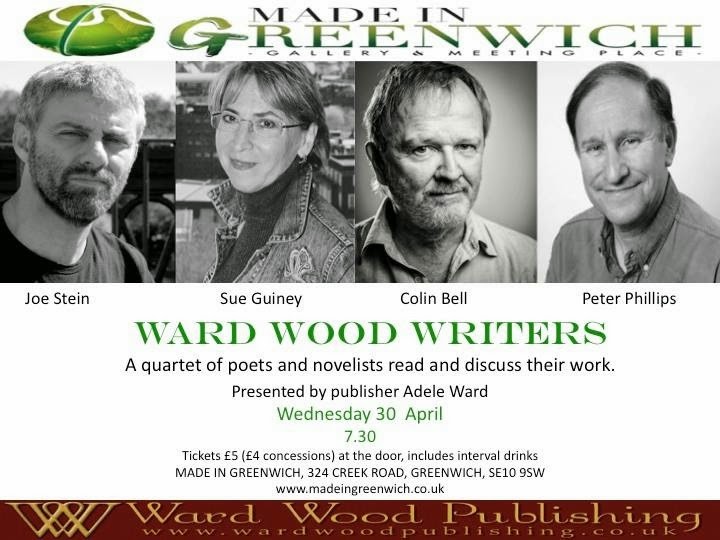

I’m going to be appearing with three of my fellow Ward Wood writers in Greenwich, London on 30th April. Come along if you can – it would be good to see you.

——————————————————————————————————–

STEPHEN DEARSLEY’S SUMMER OF LOVE BY COLIN BELL

My novel, Stephen Dearsley’s Summer Of Love, was published on 31 October 2013. It is the story of a young fogey living in Brighton in 1967 who has a lot to learn when the flowering hippie counter culture changes him and the world around him.

It is now available as a paperback or on Kindle (go to your region’s Amazon site for Kindle orders)

You can order the book from the publishers, Ward Wood Publishing:

…or from Book Depository:

…or from Amazon:

.jpeg)