I spent some interesting time in Richmond, the State capital of Virginia in the very hot Summer of 1995. It was hot for me anyway being a mere Brit on a foreign trip.

I spent some interesting time in Richmond, the State capital of Virginia in the very hot Summer of 1995. It was hot for me anyway being a mere Brit on a foreign trip.

I was working on a television programme about the crime writer Patricia Cornwell who is based in the city and whose books concentrate on the darker side of life, usually starting at the city’s morgue and getting more gruesome as they develop.

It was my first significant visit to the American South and, in two visits that year, I had many deeply memorable experiences. Some of them stay in my mind with vivid images of things I wish I had never seen.

More of that, maybe another time. Let me leave that side of my trip alone with just the thought that I spent time in the mortuary, got shot at on night duty with a young Richmond cop and I witnessed crimes both being committed but also violence’s grisly aftermath.

More of that, maybe another time. Let me leave that side of my trip alone with just the thought that I spent time in the mortuary, got shot at on night duty with a young Richmond cop and I witnessed crimes both being committed but also violence’s grisly aftermath.

I don’t know what the figures are now but in 1995 Richmond held the unfortunate record of having the highest murder rate per capita in the United States. That, of course, was quite something. First impressions of Richmond were of a gentle, old fashioned city with beautiful buildings which reminded me of home. All over Virginia too, I was greeted with real enthusiasm by people who were attracted by my English accent. The old ties with Britain seemed strong here – almost to the point of weirdness.

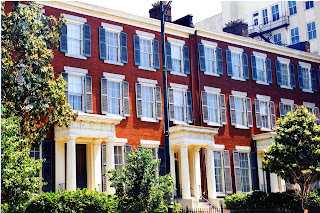

First impressions of Richmond were of a gentle, old fashioned city with beautiful buildings which reminded me of home. All over Virginia too, I was greeted with real enthusiasm by people who were attracted by my English accent. The old ties with Britain seemed strong here – almost to the point of weirdness.

I was invited to a party held by one of the city’s institutions and, when I arrived, I discovered that it was being held in my honour. Everyone was given a dry martini because that, they assumed was my tipple of choice. They didn’t know me, of course, but I was treated like an old friend and given some very dubious compliments. I wasn’t pleased to be told that I sounded like Prince Charles and I was amazed when one woman said that Richmond had never wanted to have independence from Britain.

I was invited to a party held by one of the city’s institutions and, when I arrived, I discovered that it was being held in my honour. Everyone was given a dry martini because that, they assumed was my tipple of choice. They didn’t know me, of course, but I was treated like an old friend and given some very dubious compliments. I wasn’t pleased to be told that I sounded like Prince Charles and I was amazed when one woman said that Richmond had never wanted to have independence from Britain.

These people, I am sure, were not typical; the city seemed American enough to my untutored eyes.

Big American cars, especially the ones painted in colours that you simply never see in Britain and shiny skyscraper office blocks unashamedly dominating rows of early Nineteenth Century terraced housing.

Big American cars, especially the ones painted in colours that you simply never see in Britain and shiny skyscraper office blocks unashamedly dominating rows of early Nineteenth Century terraced housing.

By my hotel, the wonderfully atmospheric Jefferson, there was even somewhere to tie your horse.

By my hotel, the wonderfully atmospheric Jefferson, there was even somewhere to tie your horse.

There were less gracious parts of town though as I was to find out in more detail on another occasion. This end of the city, with, as far as I could see, its entirely black community seemed a thousand miles away from the elegance of the buildings around my hotel.

There were less gracious parts of town though as I was to find out in more detail on another occasion. This end of the city, with, as far as I could see, its entirely black community seemed a thousand miles away from the elegance of the buildings around my hotel. Yet again, on my visits to the United States, I was warned against walking in the “dangerous” parts of town. These were always the areas which I could only describe as black ghettos and, in Richmond, they were no more prosperous than the black areas I had visited in Philadelphia, Chicago and Washington D.C.

Yet again, on my visits to the United States, I was warned against walking in the “dangerous” parts of town. These were always the areas which I could only describe as black ghettos and, in Richmond, they were no more prosperous than the black areas I had visited in Philadelphia, Chicago and Washington D.C.

Sadly, there were the same visible signs of alcohol as the succour of those who were bumping along the bottom of the barrel of American life. I may be wrong but it struck me as ominous that the street drunks in Richmond were always black, just as they were always Latino in California and Native American in Minnesota.

Sadly, there were the same visible signs of alcohol as the succour of those who were bumping along the bottom of the barrel of American life. I may be wrong but it struck me as ominous that the street drunks in Richmond were always black, just as they were always Latino in California and Native American in Minnesota.

Finding these old photographs in the loft reminds me of one of those days, I have been lucky in my work, when I had a day free just to roam around an interesting city away from home. It was good that this time I had my camera too.

I am thinking of a particularly hot Sunday when I was new to the city and I had no demands on my time other than trying to get to know what lay under the surface.

Yet again though I found that living in a good hotel in the middle of an American city does leave you in an abandoned world at weekends.

The shops have moved out to the malls on the outskirts and the office workers are all home in the suburbs.

This was my first Virginian Sunday, in the heat, Richmond’s sinister reputation was high in my thoughts. The new scare was drive-by shootings. I think my mind took to this too literally as I flinched whenever a car came near. Why me? Why now? I thought. Sadly that is the point of these brainless acts of violence. I just had to get used to the idea and, soon, I did.

So off I went, often through deserted downtown streets where the tarmacadam roads were melting in front of me. I headed for the charm of the cobbled streets in the old town. This was American middle class life writ large. There were even some people. Smartly dressed, or dressed with some thought at least, they came chatting as they came out of coffee shops and stepped into cars which, to my eyes, just spoke of dollars.

Others looked like they were extras from a Tennessee Williams play – maybe they were.

Others looked like they were extras from a Tennessee Williams play – maybe they were.

It was here that I recognised that the American South is its own country.

It was here that I recognised that the American South is its own country.

I had to look around for signs of life whilst remembering that this was a city with a reputation for sudden death. The calm, the heat and the eerie silence gave me presentiments of evil but this was all nonsense. I relaxed when I looked above me and saw two young men scaling a building with perilous enthusiasm.

I had to look around for signs of life whilst remembering that this was a city with a reputation for sudden death. The calm, the heat and the eerie silence gave me presentiments of evil but this was all nonsense. I relaxed when I looked above me and saw two young men scaling a building with perilous enthusiasm.

It was Sunday, gawd dammit, and folks were out having fun. It was too easy to turn every passing stranger into a murderer or a pervert or both. Maybe it was Patricia Cornwell’s fault. Her dark vision of her native country had penetrated to the roots of my usually optimistic nature.

These young men were not terrorists or robbers. There wasn’t a bomb in their rucksacks, just a rope and a sense of man pitting himself against his limitations for the sheer enjoyment of it.

These young men were not terrorists or robbers. There wasn’t a bomb in their rucksacks, just a rope and a sense of man pitting himself against his limitations for the sheer enjoyment of it.

Richmond has more calls to fame than just its unfortunate murder rate which, apparently, has accelerated due to its convenient position on the freeway between bigger conurbations to the North and South. A pick up point for drug dealers and consequently a market town for crack cocaine.

Richmond was also the centre of the drug-trade for my adolescent addiction – nicotine. Virginia tobacco, Richmond cigarettes, Lucky Strikes or Luckies, I can feel myself inhale as I say the words. A mantra still playing in my head.

I paid my respects to the cigarette manufacturers, like a member of a forbidden society and moved on to a great avenue of statues. American generals and Presidents, Southerners mostly, lined this leafy thoroughfare.

I paid my respects to the cigarette manufacturers, like a member of a forbidden society and moved on to a great avenue of statues. American generals and Presidents, Southerners mostly, lined this leafy thoroughfare.

Reminding me, if I needed reminding, that Richmond had been the capital of the Confederate South during the American Civil War.

Reminding me, if I needed reminding, that Richmond had been the capital of the Confederate South during the American Civil War.

Far be it from me to intrude on a nation’s grief but when I was in Virginia I found that people still talked of the war as if it was still being fought. Between 1861 and 1865, 620,000 soldiers were killed, the nation was divided, slavery abolished and some legends, on both sides, were born.

Far be it from me to intrude on a nation’s grief but when I was in Virginia I found that people still talked of the war as if it was still being fought. Between 1861 and 1865, 620,000 soldiers were killed, the nation was divided, slavery abolished and some legends, on both sides, were born.

It was the biggest ever blood-letting on American soil and the losing side, the Confederates from their base here in Richmond, suffered a defeat which many of its supporters still lament today.

I visited the graveyard where many of those Confederate soldiers lie buried. It was a bad day to have chosen, maybe. Death was already in the air for me as I walked around this brooding city, but here, alone in the beautiful cemetery, I felt as if these graves were newly dug.

I visited the graveyard where many of those Confederate soldiers lie buried. It was a bad day to have chosen, maybe. Death was already in the air for me as I walked around this brooding city, but here, alone in the beautiful cemetery, I felt as if these graves were newly dug.

Historians debate the issues involved but few deny the bravery of the young soldiers on both sides of this conflict. The Southern troops, almost certainly destined to lose from the start, were defending, no question, an abhorrent principle, but the responsibility must lie with their leaders.

If these men had not shown remarkable courage and determination then there would now be no debate and there would be no romance attached to those legends of the Old South.

I wondered if Private Daniel Rudisill had died from injuries sustained at the Battle of Gettysburg, just two weeks earlier and it was, somehow, moving that someone had planted that much derided flag next to his grave.

I moved on back into town but the military mood persisted.

I moved on back into town but the military mood persisted.

I could hear what sounded like an army band playing stirring arrangements of George Gershwin. Still with plenty of time on my hands I wandered over to see a band practising amidst a sea of red and blue table clothes. Something patriotic was going to happen, obviously.

I walked into the enclosure by the Capitol building. My camera and spare lenses round my neck worked as a pass as far as the security men were concerned but I was just being idly nosy. One of the guards gave me a suspicious look when I went on up the steps to where a large crowd was gathering but he looked away and I went off to find out what was going on.

I walked into the enclosure by the Capitol building. My camera and spare lenses round my neck worked as a pass as far as the security men were concerned but I was just being idly nosy. One of the guards gave me a suspicious look when I went on up the steps to where a large crowd was gathering but he looked away and I went off to find out what was going on.

I passed two armed policemen. I am still uneasy about policemen with guns. I am sure that I look like a criminal the moment I see a policeman and if I ever panicked and ran, I would be sure to get a bullet between my shoulder blades.

I passed two armed policemen. I am still uneasy about policemen with guns. I am sure that I look like a criminal the moment I see a policeman and if I ever panicked and ran, I would be sure to get a bullet between my shoulder blades.

On this occasion they weren’t looking at me, so I moved on.

Much more scary was a group of mature women, apparently they were members of that formidable organization, The Daughters of the Revolution which is only open to women with a provable blood link back to people who made a contribution to the American War of Independence.

Much more scary was a group of mature women, apparently they were members of that formidable organization, The Daughters of the Revolution which is only open to women with a provable blood link back to people who made a contribution to the American War of Independence.

If there was ever another war between Britain and the United States, these women surely should be in the front line.

I then passed more familiar types,cameramen, television reporters and journalists, including this fine specimen with his movie-style bow tie

I then passed more familiar types,cameramen, television reporters and journalists, including this fine specimen with his movie-style bow tie

And, forgive me, ma’am, if I am wrong, but this woman was certainly a political spokesperson in mid-brief. I was now in a large gathering of uniformed men and frightening women with gigantic hair-dos.

And, forgive me, ma’am, if I am wrong, but this woman was certainly a political spokesperson in mid-brief. I was now in a large gathering of uniformed men and frightening women with gigantic hair-dos.

Undaunted, my curiosity took me on to see who was the centre of attention – it certainly wasn’t me.

The uniforms, on closer examination, belonged to members of the emergency services.

The uniforms, on closer examination, belonged to members of the emergency services.

I followed them in and found myself a chair in a space filled with intense servicemen and their families. I felt like an intruder but then again, I was one.

I followed them in and found myself a chair in a space filled with intense servicemen and their families. I felt like an intruder but then again, I was one.

All the focus was on a man making a speech. He was praising the emergency services for their bravery and I felt that I was witnessing a moment from the Civil War all over again. I had missed his opening remarks but I soon found out what it was all about.

All the focus was on a man making a speech. He was praising the emergency services for their bravery and I felt that I was witnessing a moment from the Civil War all over again. I had missed his opening remarks but I soon found out what it was all about.

Speeches over, the audience rose as one and made its way down the steps to the enclosure where the band began playing again. Gershwin, of course, but this time with a babble of enthusiastic talk.

Speeches over, the audience rose as one and made its way down the steps to the enclosure where the band began playing again. Gershwin, of course, but this time with a babble of enthusiastic talk.

The big man was the Governor of Virginia, one George Allen, later to be a U.S Senator and later still to be talked of as a possible Republican candidate for the Presidency in 2008. We smiled at each other as he walked by. Why? I knew nothing about him at that time and I could feel that we would never be friends. It was remarkable though that I could have got so close to him without any security checks. Good for America I thought but I am sure that would never happen now.

Accredited journalists, news cameramen, news presenters and their teams milled around so I joined in with my camera and tried to find out what this was all about.

Accredited journalists, news cameramen, news presenters and their teams milled around so I joined in with my camera and tried to find out what this was all about.

This was July 1995. Only three months earlier, on the 19th. April, the Federal Building in Oklahoma had been blown up by a troubled loner called Timothy McVeigh. This ceremony today was to honour the emergency services from Virginia who were part of the 665 rescue workers who went to help after the explosion which killed 168 people and injured a further 800.

This was July 1995. Only three months earlier, on the 19th. April, the Federal Building in Oklahoma had been blown up by a troubled loner called Timothy McVeigh. This ceremony today was to honour the emergency services from Virginia who were part of the 665 rescue workers who went to help after the explosion which killed 168 people and injured a further 800.

It had been the worst act of terrorism on mainland America before the attacks of 9/11.

These young men in their smart uniforms looked happy and dignified, proud of what they had done. There is no question, however, that they had seen some terrible sights. Amongst the dead were 19 children and babies and three pregnant women. There was never an agreed final count of the casualties as there was an unmatched leg at the end of it all.

These young men in their smart uniforms looked happy and dignified, proud of what they had done. There is no question, however, that they had seen some terrible sights. Amongst the dead were 19 children and babies and three pregnant women. There was never an agreed final count of the casualties as there was an unmatched leg at the end of it all.

So, on this strange, sometimes surrealistic day in Richmond, I had returned to stories of more young men in uniforms. More bravery and more dreadful images of carnage.

Their families were right to be proud of them and it was good to be there to be a part of this scene recognizing bravery which, sadly, had to be repeated with even more horror just a few years later on.

Their families were right to be proud of them and it was good to be there to be a part of this scene recognizing bravery which, sadly, had to be repeated with even more horror just a few years later on.

But I could not help thinking of the connections. Young men, enthusiastic for what they believed in, the civil war soldiers, the Virginian emergency servicemen and then another young man.

But I could not help thinking of the connections. Young men, enthusiastic for what they believed in, the civil war soldiers, the Virginian emergency servicemen and then another young man.

He had been in the first Iraq War, specially commended for his effort too. He had witnessed the horrific bombing of the retreating Iraqi soldiers and returned to America, scared, emotionally unstable but armed with dangerous knowledge.

It can never be excused of course, but Timothy McVeigh, did not look that different from these young men today.

It is a frighteningly thin line between bravery and murder. We need to look out for these vulnerable people exposed to the horrors of the modern world. Death stayed in the air for me that day.