It was released to the World in Munich in 1865 but completed in the year that I am studying at the moment 1859. Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, the most talked about and written about of all operas and one which once heard changes your musical perspective permanently whether you love it or hate it.

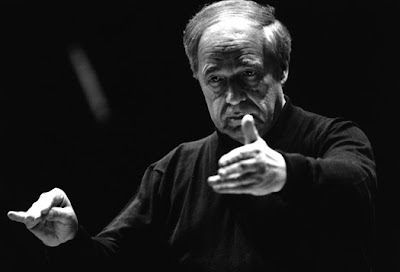

I came to it again with nervous steps in this self-inflicted music history project which has taken me chronologically through Western classical music from 1100 until, yes 1859, in just over ten years. Call me a fanatic if you must but it has been an extraordinarily interesting experience with only a bit of cheating on the way – Mahler 3, Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No. 2, some Rubbra symphonies and, sadly, a fantastic performance of Tristan and Isolde at Glyndebourne two years ago (see the picture above) which nearly blew the whole venture out of the water.

I have tried to hear each composer’s works with contemporary ears and only a knowledge of what had preceded them. So when those clever composers at Notre Dame in Paris thought of writing a second line to harmonise Gregorian chant, I was as alarmed by its modernity as much as those gallic monks must have been in the 12th. Century. Similarly, when I got to John Dunstable (c1390-1453) and his virtual “invention” of the harmonic Third, I was as thrilled by the sound as if I had been listening to the premier of Stravinsky’ s The Rite Of Spring.

I once left a cafe because it was playing a recording of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony because I was living in the musical world of 1770 and I am still holding out against a longing for the music of Stravinsky, Bartok, Debussy and Ravel – all composers introduced to me by inspired recordings or performances by the great, loved and hated 20th and 21st Century composer/conductor Pierre Boulez.

Boulez has been my guide not just in the music of Richard Wagner but he also made what I had thought to be difficult in “modern” music exciting – sexy even – and when, amazingly, he became conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra it was possible to go to the Proms and to witness the great man opening up 20th. Century classics on an absurdly regular basis. I could just pop in for a very small amount of money for never to be forgotten performances of Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloe, Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire, the Bartok Piano Concertos and, of course Debussy’s Le Mer and Images.

It was the same at The Royal Opera House Covent Garden where you could sit up in the “gods” for a brilliant and dramatic production of Debussy’s opera Pelleas et Melisande, once more with the great Pierre Boulez conducting. Those seats up there at the top of the opera house were familiar to my teenage years, Solti’s sensational performances of Wagner’s Ring cycle for starters, and it was here that I sat next to an old, very very old, Parisian woman who had flown over from Paris especially saying that she had been at the first performance of Debussy’s opera on 30th. April 1902. She told me that the Melisande that we were listening to (the Swedish soprano, Elizabeth Soderstrom) was the best that she had heard since the premiere with the legendary Mary Garden (1874-1967).

The old lady was tiny, very thin and frail, so I was concerned when after our fascinating interval chat up there in our seats, she fell asleep, her head slumped onto my arm. Should I wake her up and risk killing her with the shock or let her miss this much anticipated performance? Luckily she awoke quite soon afterwards and certainly claimed that she had enjoyed the whole thing immensely. I like to think that she had been Debussy’s last mistress but I am sure that was just my fantasy but she was certainly a part of musical history.

The old lady was tiny, very thin and frail, so I was concerned when after our fascinating interval chat up there in our seats, she fell asleep, her head slumped onto my arm. Should I wake her up and risk killing her with the shock or let her miss this much anticipated performance? Luckily she awoke quite soon afterwards and certainly claimed that she had enjoyed the whole thing immensely. I like to think that she had been Debussy’s last mistress but I am sure that was just my fantasy but she was certainly a part of musical history.

In case you wonder why this has anything to do with Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, well it was, of course, Pierre Boulez who first encouraged me to enjoy the famous prelude which had taken on the coating of a bitter pill with all those music lectures about how “important” it was as the beginning of 20th. Century music.

Like the poetry of John Donne, I came to Tristan too early in my life before I realized not only that Donne and Wagner’s Tristan are pure sex but also that sex in both their opinions was a great deal more profound than any schoolboy could ever imagine. Boulez opened my eyes to many things!

If Boulez liked Wagner, just as he loved Stravinsky and Debussy, then, I thought, why should I hold out against music’s great monster?

After the prelude, with its refusal to let any of the harmonies resolve, we are expected to sit through four hours of music, wonderful music no doubt, until that great moment of resolution, or transfiguration, happens right at the end with Isolde’s long, passionate and, let’s face it, mystical but also orgasmic final scene.

I hadn’t heard it before when I sat down to listen with a friend at school….just like The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper and Debussy’s Le Mer, it was a seminal moment. When the music reached its last dozen or so bars, my friend ejected the vinyl lp saying that he couldn’t take it any more. Without realizing it, he had thrown us back to that unresolved, yearning prelude where Wagner’s “full-blooded musical conception” had begun.

OK, Tristan is undoubtedly a revolutionary moment in music history – those unresolved chords and cadences and the most extreme chromatic writing that had ever been heard up until then – but the writing was there for a purpose: to express in music what Wagner saw as humanity’s most profound essence, love and sex united in a mystical union beyond our everyday experience in some paradise world where body is finally united with imagination in a perfect expression of love. Those four hours of musical “yearning” and tension may have brought in a new musical era free from a centuries old harmonic tradition but for the rest of us, absorbed, shocked even by the work’s unique passion and sublimity, it is just about the most visceral experience it is possible to experience with just your ears.

It was a fantastic moment to listen to it again as a part of my on-going musical project but when I sit down and think about it, it is beyond history just like the supreme artistic achievements of Michelangelo, Shakespeare and, well, I will leave the others for you to fill in.

I was, as I told you, lucky enough to see a great production of Tristan a few years ago in the little, acoustically perfect opera house at Glyndebourne, just down the road from here, with the ideally cast Nina Stemme as Isolde (it has been released on DVD and you really should see it) but if I have to look to one of the most memorable concerts in my life, it would have to be when I went to hear one of the greatest of all Wagnerian sopranos, Birgit Nilsson, singing the Tristan Liebestod, conducted by Rafael Kubelik, in her farewell recital at the Royal Albert Hall, London in 1982 when her voice showed absolutely no signs of strain after a long career indomitably and flawlessly riding high above Wagner’s massive orchestras. It was a dangerous thing for the audience that night, when we left, it was difficult to look people in the eye because we had all been taken to the X-rated adult world of Wagner at his best and at his most provocative.

Here she is, at the height of her career singing with the great German conductor Hans Knappertsbusch. Has anyone ever done this music better?