The great English poet Philip Larkin wrote: “Sexual intercourse was invented in 1963, a bit too late for me.”

Well, I have news for him but maybe that is a bit too late for him too as he died in 1985. I think after much research into various romantic operas that sexual intercourse was probably invented in 1859.

There was definitely something in the water that year which saw the creation of Gounod’s Faust, Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and Verdi’s Un Ballo In Maschera. We should not be taken in by the respectable faces that look down at us from Victorian portraits – Dorian Gray is lurking in most of them.

1859 is mostly remembered as the year that Charles Darwin (1809-1882) published his On The Origin Of Species which got the church’s knickers into a twist and raised more than a few eyebrows when respectable folk read about their ape-like origins in the morning papers.

Maybe, in 1859, people were getting in touch with their animal side.

Certainly those pale faced lovers who pined away unrequited in the romances of the early 19th. Century are replaced, at least in the three great operas from this year as full-blooded ape-descended mammals who can’t wait to get their knickers down.

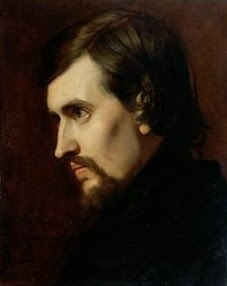

French composer Charles Gounod (1818-1893) was just the kind of guy who would have been rocked by Mr. Darwin’s theories. He was a devote young man who studied to be a priest before animal stirrings led him to some of the more exotic salons in Paris. From then onwards, if he had played that game of plucking petals from a daisy, it would have been: God, Sex, God, Sex etc. etc. before old age, as is often the way, saw him return to religiosity big time.

In 1859 he wrote his most famous and his best opera. Faust, often seen as a trivial and embarrassing reduction of Goethe’s great verse drama, is in fact a brilliantly paced, melodically inventive and theatrically gripping drama about sex and God.

There was an impressive production of it a couple of years ago at Covent Garden (available on DVD I believe) where the character of Faust was played as the old Gounod locked into his life as an elderly and religious master of the cathedral organ wishing for his youthful libido to return. When it does, through the workings of a wonderfully showbiz devil (a perfectly cast Bryn Terfel), the young Faust cartwheels across the stage in what must have been a first for an operatic tenor (in this case the athletic Roberto Alagna).

The opera for all its hit numbers reaches its high point when Faust and his ideal love, Marguerite, meet in the garden, declare their love and, yes (well off-stage but we know what’s going on), get their knickers off. Here Gounod’s inspiration reaches an inspiration maybe not seen again in his work. There is no pretence here, love and sex are unquestionably joined in an ecstatic scene which leaves no doubt in our minds that sexual intercourse is an urgent necessity for these two.

God fights back of course and the “redemption” scene at the end shows Marguerite, who has killed her baby, been imprisoned and condemned to death, being accepted into Heaven by a choir of delighted angels. I am with the devil at this moment, who is telling the lovers to get the hell out of there. The text shows a God 1 Satan 0 victory but the music plays a different tune. That Covent Garden production ended impressively in a most satisfying way with the old Faust once more playing the organ and dreaming of erotic love.

Another opera completed in 1859 is Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, possibly the supreme operatic work and certainly the most profound in its depiction of erotic love. I discussed it in a blog not long ago (30th. September, Love’s Transfiguration in Wagner’s Erotic Imagination) so I will not dwell on it here. It strikes me in the context of the other two operas, that it is no coincidence that it too belongs in Darwin year.

Wagner had none of Gounod’s troubles about God, he had grander ideas and less scruples about fulfilling his erotic imagination. If sex and God were seen as contradictions in his era then he would simply rewrite religion. So out goes God and in comes Sexual Love as the new route to Paradise. Darwin’s noble apes, Tristan and Isolde, show us that humanity can find enlightenment without recourse to superstitious body-hating mysticism.

Moving on to Verdi’s 1859 opera, Un Ballo In Maschera (A Masked Ball), with Gounod and Wagner still ringing in my ears, I was struck by how Verdi, no stranger to expressing deep human emotions, really let himself go when writing the glorious love duet in Act Two.

I used to think that Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901), Italian opera’s greatest composer was all about romantic love but listening to this scene between Riccardo (tenor) and Amelia (soprano), I realized that this was actually the first time (and maybe the last) that he wrote an opera where the erotic love between two people was the main theme of his work.

I used to think that Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901), Italian opera’s greatest composer was all about romantic love but listening to this scene between Riccardo (tenor) and Amelia (soprano), I realized that this was actually the first time (and maybe the last) that he wrote an opera where the erotic love between two people was the main theme of his work.

Looking at the great Verdi operas before Un Ballo In Maschera, shows us that it is never really the two main lovers who hold central stage together. Mostly the romantic hero (a tenor) is either a rogue (the Duke in Rigoletto), a preoccupied soldier tied to his mother’s apron strings (Manrico in Il Trovatore), a weak Daddy’s boy (Alfredo in La Traviata) or a secondary role altogether (Gabriele in Simon Boccanegra). The main duets in these operas are between father, or father-in-law, (a baritone) and daughter (a soprano) and love, always central to the heroine’s hearts, is there to be crushed by convention, power, cruelty and deceit.

In the later operas, Verdi returns to these wider issues with even Otello and Desdemona at their happiest singing nostalgically about their, up until then, happy marriage.

In Un Ballo In Maschera, man and woman are forced together by a sexual drive that they are powerless to resist. Amelia is married to Riccardo’s loyal friend and Riccardo is a young aristocrat, like the Duke in Rigoletto but this time in love more deeply than even he realizes. The plot, a victim not for the first time, of Italian censorship, has its creaky moments and it ends with Riccardo’s dying revelation that “nothing had happened” between him and the lady in question but we know that given a bit more time, the inevitable would have been consummated and celebrated no matter what the cost. We know this because Verdi was a great composer and he has written it with almost every note in this most under-rated of his great scores.

I am not saying that Gounod, Wagner and Verdi went off for that cold shower in 1860 but 1859 burned for them in a way that they never repeated. Charles Darwin didn’t cause it of course, his book was published after the ink dried on all three operas but maybe we can look back on that year not as the time when sexual intercourse was invented but when opera composers began to spell it out and to encourage us not to feel so guilty about sex or our healthy animal appetites.

In case you don’t know Un Ballo In Maschera here is the love duet sung by Luciano Pavarotti and Katia Ricciarelli both in fine voice with Pavarotti in what was for me his best Verdi role: