I ended my brief stay-at-home holiday with a walk up to the top of Chanctonbury Ring in Sussex where you can climb to a height of 783 feet above sea level and where you can see, yes, the sea but also many miles of Sussex farm land.

It was an apt place to go at the end of a week when I have been looking around Sussex, my home county, and celebrating my new-born energy after this long and boring illness that has kept me pretty close to home for nearly a year.

The Chanctonbury Ring is an hilltop which has been significant for all kinds of folk since the Bronze Age but which was named after a circle of Beech Trees planted there in 1760 by an interfering minor aristo called Charles Goring who wanted to leave his mark on an ancient site.

The famous 1987 hurricane did what I would have done and blew them all down but, sadly, there has been a replanting and one day, Charles Goring’s blot will be back on the landscape.

I would have preferred its pre-1760 look with the ancient hilltop as it had been for millenia – a bald-headed highpoint on the top of Sussex.

I would have preferred its pre-1760 look with the ancient hilltop as it had been for millenia – a bald-headed highpoint on the top of Sussex.

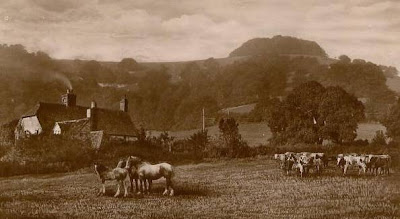

Anyway, beginning in the foothills on a blustery and dramatically clouded day, the sun burst through for just long enough to show off Sussex’s high summer golden harvest.

With the now ubiquitous cylinder bales which replace the old stacks which I used to play on when I was a kid. I remembered that smell though, of sun dried hay, as I walked on up the hillside path.

With the now ubiquitous cylinder bales which replace the old stacks which I used to play on when I was a kid. I remembered that smell though, of sun dried hay, as I walked on up the hillside path. Sussex in August is painted gold even on the dullest of days so I was not depressed by the large black clouds that were circling overhead.

Sussex in August is painted gold even on the dullest of days so I was not depressed by the large black clouds that were circling overhead.

I walked past a field of long horned cattle and met once more this week the sad eyed gaze of a young bull.

I walked past a field of long horned cattle and met once more this week the sad eyed gaze of a young bull.

I don’t suppose that he knew that this is an ominous place for bulls as it is suspected that the remains of a Roman temple found at the top was dedicated to the mysterious god Mithras who is depicted in the art of the period as a young warrior sacrificing a sacred bull and releasing the fruitful Earth.

I don’t suppose that he knew that this is an ominous place for bulls as it is suspected that the remains of a Roman temple found at the top was dedicated to the mysterious god Mithras who is depicted in the art of the period as a young warrior sacrificing a sacred bull and releasing the fruitful Earth.

The cult of Mithras was popular among Roman soldiers who worshipped their young warrior god in the dark in cave-like temples. No one really knows what they got up to but whatever it was it used to happen right up there at the top of this hill from the First til the Fourth. Centuries AD.

I spared the bull that knowledge and walked on up the path which was soon totally overhung by dense of foliage as the hillside became woodland – green and cool even when the summer sun illuminated the cornfields beyond.

This was the woodland world of English legends. The greenwood, a place of magic, of adventure and secrecy so it is no surprize to find the evil looking berries of the wild arum glowing in the undergrowth of ivy. This plant, with its many sexually explicit folk names based on its rude appearance, is as poisonous as it looks. I am sure that it must have found its way into many a witch’s cauldron along with eye of toad and puppy dog’s tails.

This was the woodland world of English legends. The greenwood, a place of magic, of adventure and secrecy so it is no surprize to find the evil looking berries of the wild arum glowing in the undergrowth of ivy. This plant, with its many sexually explicit folk names based on its rude appearance, is as poisonous as it looks. I am sure that it must have found its way into many a witch’s cauldron along with eye of toad and puppy dog’s tails.

All that’s red is not poisonous though and the abundant rose hips that liven the green hedges at this time of year are in fact a good source for Vitamin C whether in a soothing cup of tea or as the most delicate of jams. I suppose witches probably enjoyed a nice cup of tea after all that cauldron stirring.

All that’s red is not poisonous though and the abundant rose hips that liven the green hedges at this time of year are in fact a good source for Vitamin C whether in a soothing cup of tea or as the most delicate of jams. I suppose witches probably enjoyed a nice cup of tea after all that cauldron stirring.

I was now a long way up the hill and I could only catch glimpses of the open countryside beneath me.

I was now a long way up the hill and I could only catch glimpses of the open countryside beneath me.

And then I was there – on top of the hill and on one of those white chalk paths that make up the South Downs Way that stretch for 160 kilometers all the way from the white cliffs of Beachey Head in East Sussex to the ancient cathedral city of Winchester in Hampshire.

And then I was there – on top of the hill and on one of those white chalk paths that make up the South Downs Way that stretch for 160 kilometers all the way from the white cliffs of Beachey Head in East Sussex to the ancient cathedral city of Winchester in Hampshire.

One day I would love to do the whole length on a mountain bike or on horseback.

The wind howled from the West and the clouds glowered but it was still high summer as you could tell from the wild flowers in the meadow grass. Yellow buttercups, mauve clover and the pale blue of harebells give the chalk grasslands up here a bejeweled appearance.

The wind howled from the West and the clouds glowered but it was still high summer as you could tell from the wild flowers in the meadow grass. Yellow buttercups, mauve clover and the pale blue of harebells give the chalk grasslands up here a bejeweled appearance.

Nothing is gentler than the tiny harebells that blow with the wind on their impossibly threadlike stems.

Nothing is gentler than the tiny harebells that blow with the wind on their impossibly threadlike stems.

In their way they are just as tough as these magnificent wayside thistles.

In their way they are just as tough as these magnificent wayside thistles.

The ground was so full of interest that I almost forgot to look at the view which to the North took your gaze for miles across the Weald valley

The ground was so full of interest that I almost forgot to look at the view which to the North took your gaze for miles across the Weald valley

and to the South far out to sea which on this gloomiest of days still shone like silver on the horizon.

and to the South far out to sea which on this gloomiest of days still shone like silver on the horizon.

The top of the hill, the so-called Chanctonbury Ring, is where we should all stand and contemplate. We are not the first to do so, of course; those Bronze-Age flint carvers who left their weapons scattered in these fields, then Iron-Age warriors who built their formidable fort and, after them those Mithras-worshipping Roman soldiers, all of us must have stood here at different times thinking about our place in the long history of this mysterious place.

The top of the hill, the so-called Chanctonbury Ring, is where we should all stand and contemplate. We are not the first to do so, of course; those Bronze-Age flint carvers who left their weapons scattered in these fields, then Iron-Age warriors who built their formidable fort and, after them those Mithras-worshipping Roman soldiers, all of us must have stood here at different times thinking about our place in the long history of this mysterious place.