All this business of Silvio Berlusconi’s nudist parties and the former Czech prime minister, Mirek

Topolanek’s capacity for fun has put tomorrow’s elections for the European Parliament into a new light. Mr. Topolanek, who left office last month after a no-confidence vote in the Czech parliament, was also the current President of the European Union – a job which moves between countries every six months and I am sure he must have put a bit of ginger into some of those boring EU summit meetings with his flirtatious charm. His departure deprived him of what might have been a newly erotic experience even for him but, sadly, Silvio Berlusconi has decided against his plan of selecting show girls and models to stand as Members of the European Parliament.

In Britain, tomorrow’s vote doesn’t seem to be anything to do with Europe at all. No one in the main parties is talking about it and neither are the press – apart from Signor Berlusconi’s of course but that is a different kind of party.

We have the United Kingdom Independence Party – inelegantly known as UKIP – who want us to leave Europe altogether but that is about it and they are all silly people anyway. The others are either too busy worrying about their internal problems (Labour) or too frightened to mention Europe because it is an issue which divides them (Conservative). The Liberal Democrats have always been enthusiasts for the EU even, maybe, closing their eyes to the many inadequacies in its cumbersome and fat-bellied parliament.

It is a pity that we Brits don’t really have a chance to vote for anyone who might insist on the same sort of constitutional changes in the European Parliament which are, apparently, going to happen in our national one. We haven’t got anyone with any likelihood of getting elected who could represent Britain’s interests in the debate about the new European Constitution either. Some countries have voted against it and a majority of Europeans are also against it but our rulers and parliamentarians are going to force it through anyway. It would be such a breath of fresh air if democracy could enter the European system at this level but, sadly, I think, us the voters are seen as being much too stupid to have an opinion on this one.

With the pointlessness of it all, I was hoping that we might have had some showgirls or boys put up for election here too – at least that might have been more fun.

I suspect that the malaise about Europe in Britain is not reflected in those Eastern European countries that were formally inside the Soviet Union. They didn’t have the luxury of elections until they gained their freedoms.

You only have to walk through Wenceslas Square in Prague or its equivalent in Budapest to feel the malevolent tread of invading armies’ boots. First it was the German Third Reich and then, without even a pause, Stalin’s Russia.

As is now well-known, the former Czechoslovakia finally won its freedom in November 1989 with the so-called Velvet Revolution when the people took to the streets and their numbers forced a change of government.

I was lucky enough to go to Prague almost exactly a year later when I was able to witness first hand the excitement and expectation that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The World, pre-Al Queda, was going to be a peaceful planet, and, if Prague was anything to go by, a place where we would all love each other and celebrate the joys of life in the arms of benign Capitalism.

Well, we have had to revise our expectations but I for one will not be able to forget that surge of optimism that I saw on the streets of Prague in November 1990.

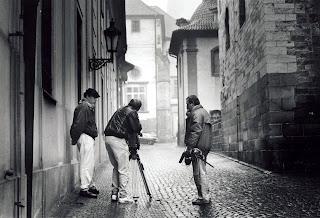

I was making a film with the Czech conductor Libor Pesek (see below) who was currently the musical director of Britain’s own Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra. The film was a musical tale of two cities and I was fortunate to see Prague through Mr. Pesek’s eyes.

I also had the chance to borrow a decent camera loaded with black and white film and I have recently found some of the photographs I took on that trip. I was nervous about using an unfamiliar format so there are not nearly as many pictures as I would now have liked to have taken but, here are some of them anyway.

I also had the chance to borrow a decent camera loaded with black and white film and I have recently found some of the photographs I took on that trip. I was nervous about using an unfamiliar format so there are not nearly as many pictures as I would now have liked to have taken but, here are some of them anyway.

First of all it should be said that Libor Pesek was the first classical music conductor that I had ever spent “down time” with. I had grown up with the prejudice that great musicians usually had foreign names and that they were almost certainly forbidding and remote geniuses.

Libor Pesek, who started his musical career as a trombonist in a jazz band, was not at all like my naive stereotype. Going to a jazz club with him was a revelation. He was the first conductor in my experience, to wear jeans and the only one who has ever queued up at a bar to buy me a drink.

He was still vibrant with the excitement of the Velvet Revolution and his animated tour of the city filled me with hope for the future both of the former Soviet Block countries and the democratization of classical music. We had a great time.

Filming some street scenes, we were often standing in the middle of the road, getting in people’s way, and, yes, probably, intruding at a nation’s party but we were greeted with real enthusiasm, well, at least according to the two dynamic young men who were acting as our interpreters and who also took us out on the town.

Filming some street scenes, we were often standing in the middle of the road, getting in people’s way, and, yes, probably, intruding at a nation’s party but we were greeted with real enthusiasm, well, at least according to the two dynamic young men who were acting as our interpreters and who also took us out on the town.

The warmest and also most embarrassing welcome was from an old woman who came up to me in the middle of the shoot and insisted that I went with her. She held my hand and walked me briskly into a local supermarket with our interpreter in tow.

Standing next to me, surrounded by morning shoppers, she raised her voice and started shouting in unfathomable Czech. Everyone clapped and I smiled and bowed feeling that that was what appropriate.

The interpreter told me afterwards that she had introduced me as an Englishman and she then went on to say that she wanted to thank me for what my nation had done to help them during the Second World War.

I had taken the praise for something that had nothing to do with me and that had happened long before my time I know but it was moving to be a part of that unexpected joining of hands and that meeting of smiles.

Change was happening wherever I went. Construction works, the erection of new buildings and the demolition of old Soviet ones seemed to be going on on every street corner. I felt as if streets would look entirely different even if I had only just walked around the block.

Change was happening wherever I went. Construction works, the erection of new buildings and the demolition of old Soviet ones seemed to be going on on every street corner. I felt as if streets would look entirely different even if I had only just walked around the block.

That sense of dynamic change also struck me when I wandered around the magnificent square that holds the government buildings and where the film Amadeus was made. It was a drizzly day, I was admiring the architecture and photographing the rookie soldiers on guard duty when a car drew up. Out came a man in corduroy trousers and a less that new pullover with an old leather bag under his arm. He made his way in through a door just as I recognised that he was the new president, Vaclav Havel. Just like Mr. Pesek, there was no time for pomposity and no thirst for it either. No time for a photo either, dammit.

I have been back to Prague since and I know that it has moved on in these years, not always I suspect for the better. Maybe some of the changes brought about by the subversive revolution of materialism have corrupted what seemed in that early period as a collective wish for equality and freedom.

I have been back to Prague since and I know that it has moved on in these years, not always I suspect for the better. Maybe some of the changes brought about by the subversive revolution of materialism have corrupted what seemed in that early period as a collective wish for equality and freedom.

On a later visit, I came across a group of drunken English lads on a raucously wild “stag night”. Prague is now an increasingly popular destination for English boozing and vomit. They were all happy enough but as they staggered blindly down the street, I remembered going to a ballroom in Prague in 1990 where young couples came to dance in a chaperoned environment where the boys were even made to wear gloves when dancing with members of the opposite sex.

Watching that generation of young lovers, all with that remarkable gift of beauty that Czech blood seems to carry with it, I was impressed by its erotic charge. It was like returning to the Nineteenth Century where subtleties between attracted parties often expressed much steamier thoughts.

I assume that such events are now a thing of the past, probably rightly so, and that the informality of Maestro Pesek and President Havel have won the day. I would love to think though that change for Prague doesn’t just have to be a vulgarisation of its culture. Let’s hope that Mirek Topolanek hasn’t converted too many of his supporters to the cynical pleasures of his friend, Silvio Berlusconi.

Let’s hope too that we, that impressive mix of cultures and talents, the Czechs, the Slovaks, the English and all the rest of us, could try to get a better parliament to represent us when we go out to vote tomorrow. It would be a terrible waste if the only ones talking about the European Union are the reactionaries, the nay-sayers, the fat cats and their fellow-travelers on the gravy train to Brussels. All of us deserve something better.

So, before you go, here is Libor Pesek conducting the sweetly sublime Czech composer, Antonin Dvorak’s Stabat Mater. Don’t be put off by Mr. Pesek’s white tie and tails.

So, before you go, here is Libor Pesek conducting the sweetly sublime Czech composer, Antonin Dvorak’s Stabat Mater. Don’t be put off by Mr. Pesek’s white tie and tails.