It’s the oldest ducal palace in Italy and maybe the least visited but also one of the most magnificent. The Palazzo Ducale in Urbino was designed by the Dalmatian architect Luciano Laurana (c.1420 -1479) known for his elegant and airy designs. This one, built on solid rock, is the very symbol of the Italian Renaissance and Laurana’s work was soon emulated by many much more famous Italian cities. It isn’t easy to get to without a car because it has no railway connection and can only be reached by rather charming and winding roads that take you into the heart of the region of Eastern Italy known as Le Marche. I had to take the bus from my rented holiday house in the small village of Gabicce Monte to Pesaro where the “rapide” bus was to whisk me away to Urbino in forty minutes. It didn’t arrive of course, as was often the case with buses in these parts so I ended up traveling all the way on a stopping bus but, hey, what’s the rush if you’re being driven through some of Italy’s most beautiful countryside.

When I finally arrived, hot but excited, I was glad that Urbino is so difficult to get to because this tiny University town was practically empty of tourists and I often had the ducal palace all to myself with plenty of time to admire Luciano Laurana’s gracious lines. Architecture, yet again on this trip, made all the more beautiful when contrasted by vivid blue Italian skies.

The absence of hordes of tourists and the fact that Urbino is largely pedestrianised, meant that a stroll round town was often only accompanied by bird song and the gloriously inventive carillon from the palaces’ clock tower. Very soon, I was on Urbino time.

Walking around, the palace is visible from almost every angle.

I was sad to find that the scaffolders had got to the front of the palace before me but even that looked geometrically interesting on such a clear day.

The original construction in the 15th Century would have been much more perilous for the builders but it would be a braver man than me to clamber up and down those ladders when even ground level was high up on the hill top.

As the Biblical parable tells us, it is a wise man who builds his house on rock and the Duke of Urbino, Federigo da Montefeltro was certainly wise and is remembered as one of the great Humanist patrons of the Italian Renaissance who founded what was seen at the time as the ideal city even if he was very much the centre of his own universe and all the subsidiary buildings served his interests. Enclosed behind the city walls, the population thrived under what was recorded as his benign rule. More of that when we go inside the palace itself part of which now houses the National Gallery of the Marche with one of the most important collections of Italian Renaissance and Baroque art in the country.

The walls enclose a beautifully preserved Renaissance town and look out onto spectacular countryside with the Apennine Mountains on the horizon behind which lie Rome and Florence.

The absence of a railway line as meant that Urbino is still surrounded by unspoiled countryside that hasn’t changed much since the 15th. Century.

In the middle of town, the country is never far away making an idle stroll round town, even on the hottest part of the day, an extremely pleasant experience. There was always a surprizing view or an interesting alleyway to keep my eyes entertained.

Urbino’s town-planners knew how to offer their citizens just enough shadow to protect even the most pale-skinned of English sight-seers from getting a touch too much of the sun.

To me, at least, Urbino that day with its mix of fine architecture and Italian sunshine was pure sweetness and light.

I particularly liked the small hillside alleyways with their well-worn but cleverly designed gradations and where the light at the end of the tunnel really does draw you onwards and upwards.

In Italy the sunlight is always painting pictures.

Urbino has a youthful student population that helps stop the place feeling like it is lost in the past.

It was probably time for lunch so I headed at an excellent restaurant called Il Cortegiana http://www.ilcortegiano.it/. right across the road from the Palazzo Ducale.

Lunch was some good local wine….

…and a deliciously simple dish of gnocchi.

Waiting for another ‘rapide’ bus that would never arrive was just too much for one day so it was fortunate that Il Cortegiano had a room for the night and that, after lunch, there was somewhere for that excellent Italian habit, the siesta.

It was genuinely a room with a view being immediately across the road from the Ducal Palace but when lunch was cleared away, it was time for a little pause.

Later, that night, I continued my Italian diet downstairs in the restaurant’s garden deciding that it’s foolish to stint yourself when you are in gastronomical heaven.

Dinner was a traditional local dish, the recipe is 15th Century according to the patron – turkey and truffles with a side plate of perfectly prepared potatoes.

Oh, and some more of that rather good local wine followed by Italian brandy.

Siesta over, I awoke in that room with a view and decided it was time to go inside the Palazzo Ducale.

I could see the entrance from my window.

Once inside the powerful looking fortress walls, the architect Luciano Laurana gets in touch with his delicate side in this delightfully aery arcaded courtyard.

Where outside is all about strength, in here he shows just how much can be supported by so little. In this case some very elegant pillars, the stonework delicately colour-shaded.

Laurana knew just how much to do himself and how much to leave to the lighting genius of the sun.

It might sound selfish but it was wonderful to be able to stand here without having to share this beautiful space with anyone else.

Sometimes, rarely maybe, an architect get the proportions just right.

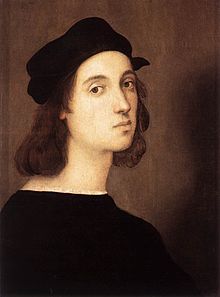

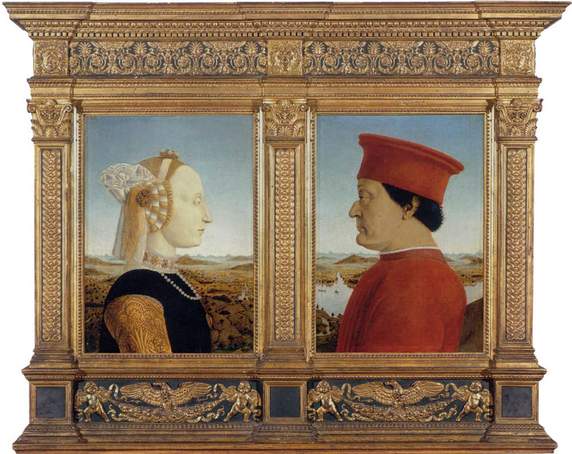

Luciana Laurana may have been a genius but we owe this example of his brilliance to his employer, the man behind Urbino, Duke Federigo da Montefeltro (1422-1482), the Humanist intellectual and mercenary soldier or condottiero, who commissioned the building and the skills of his courtiers, some of the greatest artists and intellectuals of the Renaissance period, including Francesco di Giorgio Martini who wrote his influential Treatise on Architecture here. The Duke’s portrait below, with his wife Battista Sforza, now in Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, was painted by Piero della Francesca who developed his theories of perspective in Urbino. Paolo Uccello, the artist and mathematician also developed his interest in perspective in Duke Federigo’s library. Piera della Francesca shows Federigo’s Humanist’s ‘smile of reason’ but the Duke is depicted, as all of his portraits were, in profile because he lost his right eye and the bridge of his nose in a sword fighting contest when he was a young man. He won his fortune for his brilliance in battle but his true glory was how he used his new affluence.

He created the largest library in Italy apart from the Vatican’s but, sadly, it was taken to Rome in the 18th Century by the then Pope where it is now incorporated into the Vatican Library. Urbino has suffered a number of artistic losses to Rome and Florence in particular as well as to Venice, 200 miles to the North.

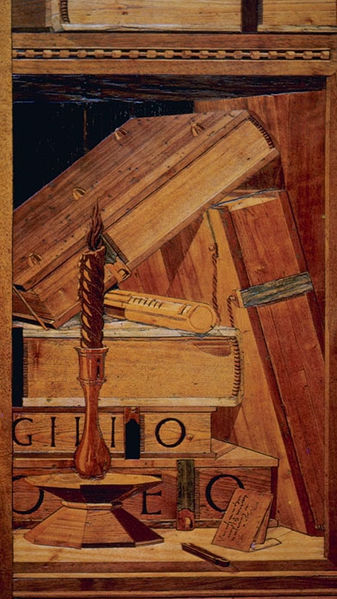

One of the most impressive rooms in the palace is Duke’s small ‘studiolo,’ his study with its intricate intarsia, or wood inlay, imitating small cupboards containing the symbols of the intellectual life.

I think we can still imagine Duke Federigo sitting in here with his books and scientific equipment and lament how few powerful leaders these days use their influence to advance mankind’s learning.

Federigo’s son, Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, (1472 – 1508) inherited his father’s title and continued to develop the Urbino court as an intellectual and artistic centre and to defend it militarily even, for a time losing his inheritance in battle to a rampaging Cesare Borgia, the son of the Borgia Pope Alexander VI. He was restored to Urbino when papal politics allowed and his court entered its golden age recorded in one of the best-selling books of the 16th Century, Il Cortigiano, The Book of the Courtier (1508 – 1528) by Baldassare Castiglioni (1478 – 1529) who was for a time a courtier at Guidobaldo’s court and who wrote this manual on how to be the perfect gentlemen. He also included a section on being a lady, modeled on Guidobaldo’s wife, the cultured and intelligent Elizabetta Gonzaga (1471-1526), daughter of the Marquess of Mantua and a formidable force in Italian intellectual life in her own right.

Guidobaldo suffered from a wasting disease and was, apparently impotent, but Elizabetta refused a divorce and stayed with her husband nursing him until his rather unpleasant death in 1508. They adopted a nephew from Guidobaldo’s sister, who was also the nephew of the new pope, Julius II, and she ruled as regent until the new Duke Francesco della Rivere (1490-1538) came of age after which Urbino fell more and more under Papal influence consequently losing its prestige.

“Then the soul, freed from vice, purged by studies of true philosophy, versed in spiritual life, and practised in matters of the intellect, devoted to the contemplation of her own substance, as if awakened from deepest sleep, opens those eyes which all possess but few use, and sees in herself a ray of that light which is the true image of the angelic beauty communicated to her, and of which she then communicates a faint shadow to the body.”

So unspoiled to this day, it is possible to think of the unchanged views from the palaces’ windows and to imagine this place in its contemplative heyday.

Forgive me for also imagining that if I’d had my room across the road in those days, I could have waved to the Montefeltro family from across the square. Then again, they might not have thought that proper behaviour for a gentleman of the court.

The furniture as well as the library was carted off to the Vatican but the papacy must have had a guilty conscience recently because the magnificent set of Flemish tapestries, above, made from Raphael’s cartoons have been returned to the palace and there are still enough paintings here to make the visit more than worthwhile with star paintings by Raphael, Giovanni Bellini and Piero della Francesca, some very fine early Renaissance triptychs and crucifixes, and a room dedicated to Urbino artist Federico Barocci (1528 – 1612) who is rapidly being “rediscovered” by the art world and admired for his lively sense of movement as a precursor of the Baroque. There is also Paolo Uccello’s Miracle of the Profaned Host, a set of six panels that formed the predella, the base of an altar. This strange, and unpleasantly anti-semitic, piece tells the story of a Parisian Jewish pawnbroker who cooks the host, or communion bread, which promptly begins to bleed. The blood flows onto the street and alerts the powers that be who come knocking like anti-Semites have during all the succeeding centuries. Putting the distasteful message to one side if we can, Uccello’s work shows his interest in experimenting with perspective and the so-called “golden line” which can also be seen in a neighbouring room in the palace in Piero della Francesca’s The Flagellation of Christ where the main story is pushed into the background with the foreground “box” dominated by three apparently unconcerned Urbinese gentlemen. The court, if nothing else, was an ideas factory. The picture that draws the most visitors, but when I visited, I was the only spectator, is the melancholy portrait of a gentlewoman, known as La Muta, The Silent One, by Raphael with its possibly deliberate references to Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Everyone needs to see this painting face to face.

It was time to leave this fascinating building and its art but I shall think of it and its beautiful rural surroundings whenever I look at the background at many a Renaissance painting and wonder if the artist was thinking of the countryside around Urbino. After-all, if they worked here at the Montefeltro court, they just had to look out of the window.

Another member of Guidobaldo da Montefeltro’s court was the composer Bartolomeo Tromboncino (1470-1535) so I will leave you with his gently evocative song “Sú leva, alza le ciglia” performed by Marco Beasley with the ensemble, Accordone.

.jpg)